|

Story by Ron Kilber

Story by Ron Kilber

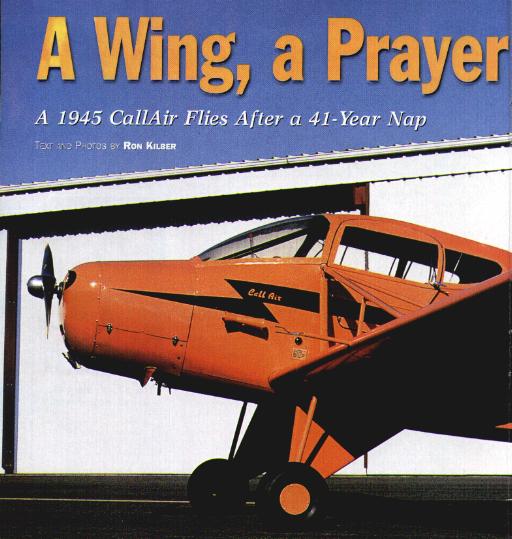

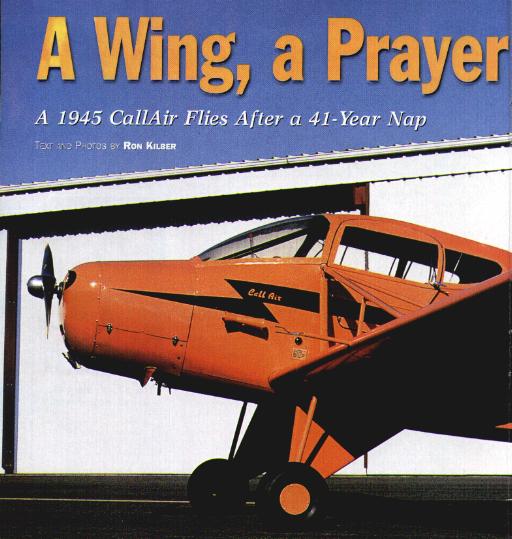

The CallAir looks remarkably familiar to me, and after I think about it a bit, the fuselage appears similar to that of a Bellanca. The tail dragger sits high off the ground (7 feet 3 inches), has that ribbed-look appearance that can only be attained from fabric-over-wood-framers, and its larger-than-normal size for a light airplane evokes a feeling of strength and endurance.

The first thing I'm impressed with after I settle into the right seat is the forward visibility -- it is phenomenal. The CallAir is a tail dragger, and even in our three-point stance in front of the hangar, I can see the waist of an individual standing not far in front of the airplane. For anyone annoyed by the massive blind spot while taxiing in many tail draggers, the CallAir solves this problem.

N34841 is surprisingly spacious inside for a two-place airplane, especially the side-by-side seating. The 43-inch-wide fuselage provides generous comfort, and we might easily fit a small, third person in the cockpit with us.

Only 7 hours have been logged since it was completely restored. In the cockpit with me today is Dick's long-time friend and flying partner, George Bormet, a 16,000-hour pilot who was the first person to share the privilege since 1957 -- to the tune of those 7 hours so far. He is of slight stature and a man of 80 years -- old enough to qualify for entry to the UFOs, the United Flying Octogenarians, the international club for pilots 80 and over.

Bormet began his flying career in 1938, when he flew the Hump in C-46 Curtis Commandos and C-47 Skytrains (aka DC-3) during World War II. He has also logged MATS hours (Military Air Transport Service) in the P-47 Thunderbolt, the P-51 Mustang, the B-24 Liberator and the B-25 Mitchell. He also flew for Flying Tigers and was a corporate pilot in the left seat of a DC-3, a B-18 and Queen Air B-80.

Coming Back to Life

For today's flight, Bormet is at the controls, while Price is in front of the propeller. He is comfortable with hand-propping the engine, which has no starter or generator. He does it effortlessly, and it only takes three tries for the 100-HP Lycoming engine to spring to life. How sweet the sound is.

Lack of on-board electrical generation was typical for the era, thus no starter, and batteries, alone, usually powered the navigation lights. Our electrical system is powered by a battery under the engine cowling. Our CallAir has no communications radio -- typical of the era -- so we are using a portable unit rigged with an intercom to headsets and microphones.

After Falcon Tower clears us to Runway 4R, George invites me to take the controls. For a pilot who has grown up on yokes and tricycle landing gear, the word "taildragger" has always been synonymous with "hard-to-control." Not so in the CallAir. It is amazingly easy to maneuver on the ground, and with the added forward visibility, there's never that angst associated with the worry of what one might run into while taxiing.

The eight-foot-wide landing-gear stance is responsible for the remarkable stability, which was often lacking in light aircraft. And the between-the-legs stick is pure enjoyment for me. (Isn't that part of why these classic airplanes are rebuilt?)

When required, heel brakes aid turning, but I have no trouble at all using the rudder pedals alone to steer or stay straight. The 360-degree tail wheel would allow me to back up, if that were possible.

After a quick run-up, we're cleared for take-off, and in no time we are rolling on Runway 4R. Just as quickly, the tail rises. At 50 mph we rotate and gain altitude in the direction of Red Mountain. We climb at 65 mph and then level off to cruise speed.

It isn't long before I regain my feel of a stick. This plane is surprisingly docile, very stable, and effortlessly controllable. It's a pure delight to fly, and I have to admit the exposed tubular frame in the cockpit adds a lot of character to this beautiful airplane, as do the strut braces on top of the low wings. The visibility directly in front to the ground is fabulous, and sitting higher than usual above the wings provides an extra sense of control and big-ship feel. I find myself falling in love with this airplane.

We want to do a power-on stall but think better of the idea after we talk about the fuel system. The tank is behind the instrument panel, where it is higher than the carburetor, providing a gravity-fed system to power the engine. No fuel pump needed here.

The only down side to such a design is that when you fly with the nose very high, as in a power-on stall, it's possible to starve the engine of fuel as the carburetor rises relative to the fuel tank. A dead-stick situation is mathematically certain when gravity can no longer feed fuel to the engine. It's better to think about such things beforehand, rather than scratch one's head in bewilderment if the engine should stop. Remember, we have no starter. Sure, we'd attempt to get the propeller going again by entering a high-speed dive, however, failing that (likely because of the tightness of a just-overhauled engine), our only recourse would be the golf course below.

It's hard to imagine that early in the restoration process, this airplane had consisted of only the cromoly steel tubing frame, which might have passed for welding art in a gallery. Today, we're actually flying in it. The miracle of flight is more of a miracle when I think of it this way.

As I now recall the details of Dick's restoration project -- more of a remanufacture -- which began with good intentions after he purchased N34841 in 1970, it occurs to me that owners of airplanes like this one might well invest 10 hours of labor for every hour that is yielded in flight time. Price has invested well over 10,000 hours in labor so far, and if he manages to fly his trophy 1,000 hours, this equations would hold true.

The author found the exposed tubular frame in the cockpit and the between-the-legs sticks to be charming and a delight to use.

The author found the exposed tubular frame in the cockpit and the between-the-legs sticks to be charming and a delight to use.

That Fateful Sale

In 1957, 13 years before Price became the owner, N34841 failed a fabric punch test after its owner, Albert Marz, flew it from Ephraim, Utah to the Paradise Airport in Arizona. It sat outside in the Arizona heat until 1961, when it was finally disassembled and the fuselage moved under a lean-to in the owner's back yard. The wings were suspended from the carport ceiling.

Eventually, the owner lost his medical license and put N34841 up for sale in 1970. When Price came along, the temptation was too great to let a perfectly good project get away for a mere $600. The airframe had 741 hours total time, and the engine had only 73 hours since a top overhaul. After all, a similar model was used in a presidential campaign with AU-H2O-64 painted on the underside of a wing. (Of course, it was Barry Goldwater, who lost to L. B. Johnson in 1964.)

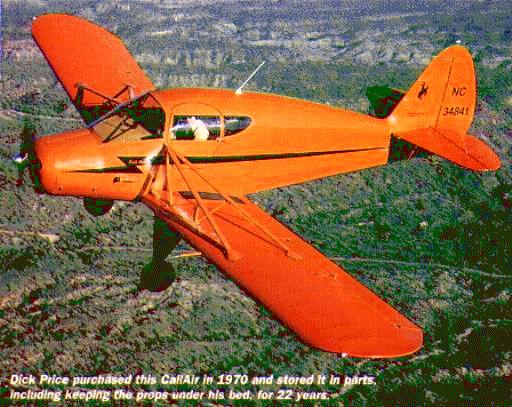

It didn't matter that Price did not have a place to store his newly acquired airplane in his townhouse. Where there's a will, there's always a way. Within weeks, he found storage at Barkers Truck Repair and Welding in Phoenix. Everything was transferred there, except for the propellers. Those stayed at home under his bed, where they remained until 1992 -- 22 years.

Getting to Work

After Barkers sold out in 1978, Dick moved N34841 to Eagle Roost Air Park, near Wickenburg, where he owns property. In September 1992, he moved N34841 to Falcon Field in Mesa and began restoration. He spent all of 1993 on the fuselage, completely sandblasting the tubular frame and replacing all of the longerons and wood formers.

Everything in each wing was replaced, except for the laminated spruce spars and the above-wing struts, which still had the original linseed oil inside. The left wing was remanufactured first, while the right served as an assembly model. In total, Price fabricated 34 new wing ribs. Each rib in turn was made of 56 parts, each of which had to be cut, fitted and glued together. The wing bows and leading edges, unavailable off-the-shelf, had to be fabricated, too. Finally, the wings were varnished, covered with fabric and finished using the Stits process.

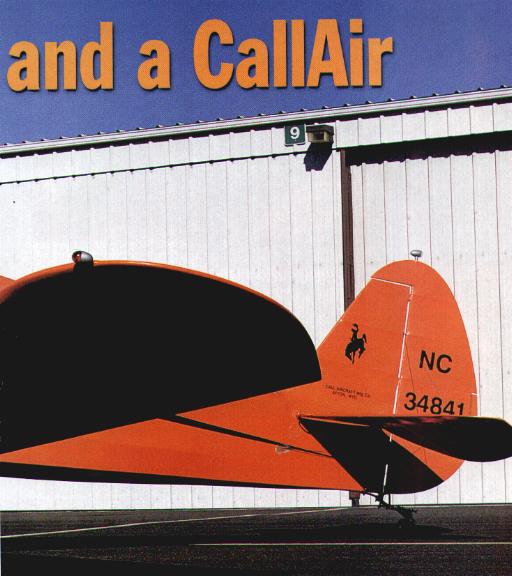

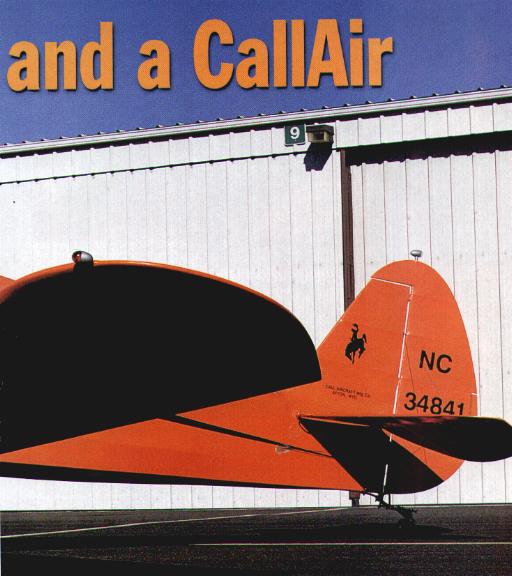

During 1997, fabric was installed on the fuselage, and the complete airplane was assembled, using the original control cables and new AN hardware throughout. For safety reasons, Price chose to change the color of N34841 from factory maroon to International Orange aircraft paint. The new windshield was made from scratch at a cost of $1,000, $600 of which paid for a new mold. This means new CallAir windshields can now be had for $500 a copy.

The fixed-pitch wood propeller, none the worse after 22 years of moving around to vacuum under the bed, pulls us along today as efficiently as it did when this airplane was first test flown by B. H. Ball on July 7, 1945.

Finishing the Flight

After about 30 minutes, George says we've put enough time on the freshly overhauled engine for today, so we head back to the barn via the Verde River until it merges with the Salt. It's surprisingly calm today, both in weather and aircraft activity, so when the Tower clears us for left traffic to Runway 4R, we have the controlled air space all to ourselves. After I turn final, we trim for 65 MPH, and then smoothly and steadily, we practically glide all the way down. On the ground, control is solid, and it's a dream to taxi back to the hangar with all this forward visibility.

According to the US Aircraft Database (as of the second quarter of 1998), 143 CallAirs remain registered, with manufacturing dates ranging from 1941 (2 of which are registered) to 1966 (one of which is registered). It's unknown how many CallAirs remain on the rolls in other countries, but there are some.

This particular airplane is an "A" Model, and only eight of these remain registered in the US. Four are approved for agriculture and pest control, and the remainder are categorized for standard flight operations. At least one ag A model is owned by the federal government, which suggests to me that it was seized after being suspected of unapproved agricultural activity (i.e. hemp-growing).

The table on page 33 illustrates the various CallAir models that have been produced and includes the number of units still registered. The CallAir was originally priced from $2,500 to $3,500. Today, such a meticulously restored airplane as this particular CallAir can easily bring $35,000 or more. Most certainly, N34841 ranks as one of the finest vintage airplanes I've ever flown.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Call Aircraft Comapany |

|

N34841 was built in July of 1945 by the Call Aircraft Company (CAC) of Afton, Wyoming, a small community of less than 2,000 inhabitants near the border of Idaho, and home of the Pitts aerobatic biplane. Afton's latitude approximates Pocatello's, its altitude is 6,234 ASL, and Jackson, WY isn't too far to the north, beyond which lies Yellowstone National Park. CAC was founded by Reuel Call in 1939, and after more than two years of engineering and flight testing, the Civil Aeronautics Administration issued a type certificate on December 7, 1941 -- the day Peal Harbor was bombed by the Japanese. Preliminary design was accomplished by Ivan Call, Reuel's uncle, and Carl J. Petersen joined the company as one of its first employees and test pilot, and is credited with origin of the name and trademark, "CallAir". Spencer Call, Reuel's brother, joined as the Chief Aeronautical Engineer, and Gaylord Swartz brought specialized welding expertise needed for fabricating assemblies made from cromoly steel tubing. World War II curtailed production because of short supplies, which were diverted to the war effort, so Call Aircraft converted its production facilities into a student-pilot repair facility for crashed airplanes, which were plentiful after virtually every airport in the country had been converted to a pilot flight school. After the war, demand increased dramatically for light aircraft, and it was a production free-for-all as many manufacturers tooled-up to meet the market needs. Piper and Cessna led the field, and the resulting competition proved difficult for the Call Aircraft Company. It's not known how many CallAirs were produced, but the numbers certainly were limited. Nevertheless, the airplane proved popular with pilots demanding an airplane that could perform well at high altitudes. In 1954, the company began manufacture of the A-4 model, which was at the time in all likelihood the first production agriculture airplane ever produced. Up to then, crop-duster capability was derived from modification of existing aircraft. During 1959, ownership of Call Aircraft was sold and transferred to one of the company's former distributors. After unsuccessful attempts at model redesign and new marketing strategies, the business failed and eventually the factory doors closed. In 1962, Intermountain Manufacturing Company (IMCO) was formed by new investors to purchase the remaining inventory and assets of the failed factory. By early 1963, new A-9 models were coming off the assembly line, and by year end about 40 units were produced and shipped. Rockwell Standard eventually purchased IMCO around 1966, and in 1967 the factory operation was relocated to Albany, Georgia. The name of the aircraft was then changed from CallAir to Aero Commander. Eventually, Rockwell sold its CallAir design and manufacturing rights to a company in Mexico City.

The CallAir Foundation and museum is what remains today to record the legacy of this wonderfully performing, high-altitude airplane. It is located in Afton, WY, and the foundation owns a 1954 A-4 CallAir powered by a 140 horsepower engine. The address is:

Reference: CALLAIR AFFAIR, Carl J. Petersen, Self-published 1990 |

| N34841's Owner |

|

Dick Price, of Phoenix, Arizona, is the proud owner of this beautifully restored 1945 CallAir, N34841, serial number 5. Dick has been a life-long aviation enthusiast and full-time since he retired in 1984. That's when he began to build his first airplane, an open-cockpit Baby Ace. When he finished the job and then savored his accomplishment by regularly flying the single-hole monoplane, he eventually decided it was time to begin work on his second project, the CallAir he acquired some 22 years earlier. Dick's first introduction to flying came from the military during WWII. His first flight ever in an airplane was in May of 1943 at Montana State College in Bozeman, where he flew the Porterfield Collegiate as an Army Air Corps student during pre-Air Force days. Eventually, he soled in a Ryan PT-22 at Hemet, California, and went on to basic flight training at Merced. But jocking in the military wasn't meant to be for Dick, as was the case for 80 per cent of his class. Nevertheless, with seventy-some hours logged, he remained in the Air Corps until the end of WWII as a cargo-load specialist. After returning to his pre-war logging job for a while and then going through college, it was a stint with a welfare department before eventually taking a position with the US government in 1955 until retirement in 1984. Dick resumed his passion for flying in 1964, and two years later earned his Private Pilot License. In 1970 he purchased as its third owner the disassembled CallAir, which he put into storage. By 1976 he was at the controls of his own experimental airplane, which he flew and maintained it in his spare time. One year later he acquired a Baby Ace in-process project, and completed it in 1985 after a year on retirement. In September of 1992, Dick began restoring his CallAir airplane, and worked steadily with the help of his friends, Gil Hallquist of Mesa, Arizona and winter-visitor Jim Sorenson of Green Bay, Wisconsin, until November of 1998 before finally completing and test-flying. George Bormet, Dick's flying partner, was instrumental with all of the flight tests, and together they successfully flew N34841 for the first time since 1957.

For the short term, Dick plans to attend the June 1999 annual CallAir Fly-In, which first began in Afton, WY on Father's Day in 1988, and has continued there every year since. |

Copyright © 1998 - 1999 Ron Kilber All rights reserved.

Ron Kilber, a private pilot since 1967, lives in Tempe, Arizona

Bob Shane is an aviation photographer who lives in Phoenix, Arizona

Email: rpknet@aztec.asu.edu

Email: bobshane@usa.net