Home

Aviation Stories

"In Memory Of"

Net Sites

Sign Guestbook

View Guestbook

Email Ron

Balancing Aircraft WheelsStory and Photos By Ron Kilber

WHO HASN'T FELT the harmonic vibration of the landing gear flapping like wings after rotating for takeoff? It happened to me recently after new "trainer" rubber was installed on my 1974 Cessna 150. Whenever I looked out the window after rotation, I saw my spring landing-gear flap in perfect harmony to that of eagle wings. Sure a quick tap of the brakes brought the vibration to an end, but it didn't solve the real problem: out-of-balance tires.

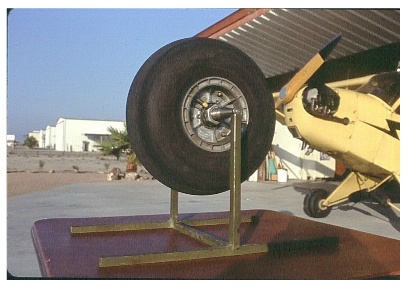

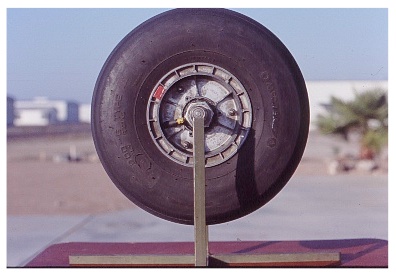

The home-fabricated wheel balancer is shown with a mounted wheel and tire.To correct the vibration, almost any FBO can balance airplane wheels. That is, if the airport has an FBO with the personnel and requisite equipment to do the job. If you're based on a remote field or live on an airpark where repair facilities are non-existent, there's another way to balance wheels without the rigamarole of flying to another airport to visit an FBO. All you have to do is build an inexpensive wheel balancer and do the job yourself!

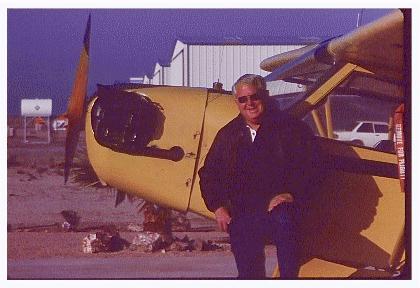

Because I live in a remote part of the Arizona desert, I don't have the luxury of a FBO on field, but I do have many neighbors who are capable and talented individuals. One such individual is retired United Airlines Captain Dennis Peck. Peck not only helped balance my tires, but also loaned me his wheel balancer so I can share its fabrication and operation with you.

Captain Dennis Peck, retired since 1994 after thirty years with United Airlines, is shown with his Piper J-3 Cub, which he has owned since 1966.During the early 1980s, while living on his ranch (and airstrip) in Elizabeth, Colorado, Peck needed a way to balance his own aircraft tires. He discussed the idea with his long-time friend, Carl Hein, who offered to "turn and thread" the mandrel on his home lathe.

Construction

The mandrel was fabricated from a piece of 1-1/4 inch bar stock, measuring 15-1/2 inches long when finished. Each end was tapered two inches to 5/15 inch shaft thickness (1/2 inch wide) to accommodate precision bearings (in this case, SNR 608 sealed, 7/8" OD, 5/15" ID).

Pecks's wheel balancer configured without a wheel mounted.The mandrel was threaded 3-1/2 inches inboard from the taper (12 threads per inch). Two sheet-metal screws (no. 6) were installed in holes drilled opposite each other 9-1/2 inches from the threaded end.

The wheel balancer component parts.To lock the wheel in place on the mandrel, two old bearings were disassembled (in this case Bower BT08125, but any will do). On either side of the tire hub, the old bearing raceways were held in place by the sheet-metal screws on one end and a steel nut (1-1/4 inch, 12-threads/inch) on the other.

A stand to support the mandrel and wheel was welded from 3/4-inch square tubing. The frame dimensions are: 12-1/2 H by 15-1/2 W inches with an 18-inch base.

The mandrel bearings fit perfectly into the top of either square tubing frame.

Balancing the Tires

While using Peck's home-made balancer, I quickly discovered the precision of his mechanism. Even without a wheel mounted on the mandrel, the shaft rotated freely until its heavy side was down. With this amount of sensitivity, I mused, my landing gear would never again flap and vibrate after rotation. Using a small amount of stick-on weight, I managed to balance the mandrel before mounting the wheel.

Note the position of the valve stem before balancing!Surprisingly, too, when I installed a wheel on the balancer, the tire gradually clocked until its heavy side was down. Just to be sure, I rotated the wheel once more, and again it stopped precisely in the same spot.

Note the position of the valve stem after balancing! For illustration purposes, the stick-on weights are shown in red and mounted on the side of the hub. It's suggested to mount the weights inside the hub.After experimenting with stick-on weights (available almost anywhere), I managed to achieve enough balance so that no matter how much I spun the wheels, they never stopped in the same place twice. It was obvious to me that my wheels would be much better off after balancing than before.

After balancing, the wheel stops in random positions.Flight Testing

After mounting and careful inspection, my landing gear no longer vibrated and flapped like wings after takeoff. (This is just what I had expected.) Instead, departure was as smooth as if I had tapped on the brakes after rotation.

There are many benefits that result from precision-balancing aircraft wheels. Not only do the tires last longer, but they will wear better because the wheels stop randomly, eliminating a heavy side from always striking the pavement first on landing.

Owner-Performed Maintenance

According to the FAA Regulations, owners may perform a myriad of maintenance procedures on production, homebuilt and ultralight aircraft.

PART 43

MAINTENANCE, PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE, REBUILDING, AND ALTERATIONSec. 43.3 Persons authorized to perform maintenance, preventive maintenance, rebuilding, and alterations.

(d) A person working under the supervision of a holder of a mechanic or repairman certificate may perform the maintenance, preventive maintenance, and alterations that his supervisor is authorized to perform, if the supervisor personally observes the work being done to the extent necessary to ensure that it is being done properly and if the supervisor is readily available, in person, for consultation.

(g) The holder of a pilot certificate issued under Part 61 may perform preventive maintenance on any aircraft owned or operated by that pilot which is not used under Part 121, 127, 129, or 135.

Sec. 43.5 Approval for return to service after maintenance, preventive maintenance, rebuilding, or alteration.

(f) A person holding at least a private pilot certificate may approve an aircraft for return to service after performing preventive maintenance under the provisions of Sec. 43.3(g).

###

Copyright (C) 2001 Ron Kilber rpknet@aztec.asu.edu RonKilber.tripod.com Non-commercial reproduction permitted in its entirety with this copyright notice intact.